Next month, the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) and #PayTheGrants will present a case to the Pretoria High Court contesting the R370 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant’s restrictions. They contend that the existing application requirements are unlawful and unfairly exclude qualified individuals.

In response, the Ministry of Finance, Sassa, and the Department of Social Development (DSD) assert that the laws uphold constitutional rights and are effective. On October 29 and 30, the Pretoria High Court will consider an appeal regarding the R370 monthly Social Relief of Distress (SRD) payment standards.

The Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) and #PayTheGrants filed a lawsuit in the Pretoria High Court in 2023 to contest rules that prevent many eligible individuals from receiving the award. The application lists the (Sassa) and the Minister of Social Development as replies. One responder is the Minister of Finance, as well.

During the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the SRD grant was implemented as a last-ditch effort to reduce severe poverty and famine. The payment period was initially scheduled from May 2020 to October 2020. However, it has been extended yearly since then. In April, the monthly payout was raised from R350 to R370. The award is only available to those with monthly incomes up to R625. Sassa checks the beneficiaries’ bank accounts monthly to see how much money they make.

Court Application:

#PayTheGrants and the IEJ contend in the court application that the government’s definition of “income” is extensive because it considers gifts and financial assistance from friends and family. They want the court to decide that the only forms of “income” are those obtained from investments, commercial ventures, or employment.

Additionally, they want the court to decide that the grant amount and qualifying income criteria should be raised to account for rising living expenses and inflation.

They further fault Sassa for using databases from the National Student Financial Aid Program, the Employment Insurance Fund, and Sars to verify income. They want the court to rule that the database verification process is illegal and unconstitutional since they claim that some databases are erroneous. They want the court to forbid bank verification because it ignores beneficiary income changes.

Unlike other social awards that may be sought in person, the SRD grant can only be applied online. Some applicants do not have online access, according to the IEJ and #PayTheGrants, and they are asking the court to decide that applications submitted in person should be accepted.

They demand that the appeals process be deemed illogical and unreasonable because they claim that the present appeals procedure prevents a grant applicant from presenting fresh evidence.

Government Response:

Ebenezer Nkosinathi Dladla, chief director of legal services at the Department of Social Development, defended the online application process in his affidavit.

“Five applicants can use one cellphone number, and the cell phone data does not require data,” he stated.

“All SRD candidates can apply using either the dedicated SRD website, which provides them with step-by-step instructions through the procedure, or the WhatsApp channel, which offers the same service. This makes the process extremely simple. Dladla stated, “This process doesn’t even take more than 20 minutes.

According to him, the SRD grant is “among the most successful” in the nation. He declared, “The online method is the most efficient and effective.” “South Africa is not only changing technologically, the entire world is too.”

Those without smartphones, he noted, “can use the cell phones of their family members, neighbors, and peers.”

“There is no complexity involved in the online application process for the SRD. In rural areas, individuals can seek assistance from the tribal authority or the village leader,” the spokesperson stated. Dladla

Dladla reaffirmed that a manual procedure would be “regressive” and cause a delay in receiving appropriate help, adding that the online method is more straightforward than visiting Sassa facilities. He rejected the accusations of unconstitutionality.

Sassa Response:

In his declaration, Brenton van Vrede, executive manager of Sassa, supported the SRD grant verification system’s use of public databases. This stops applicants from “double-dipping” when they apply for the SRD award and get funding from other government agencies.

He said that it is “reasonable and necessary” to use various databases for verification.

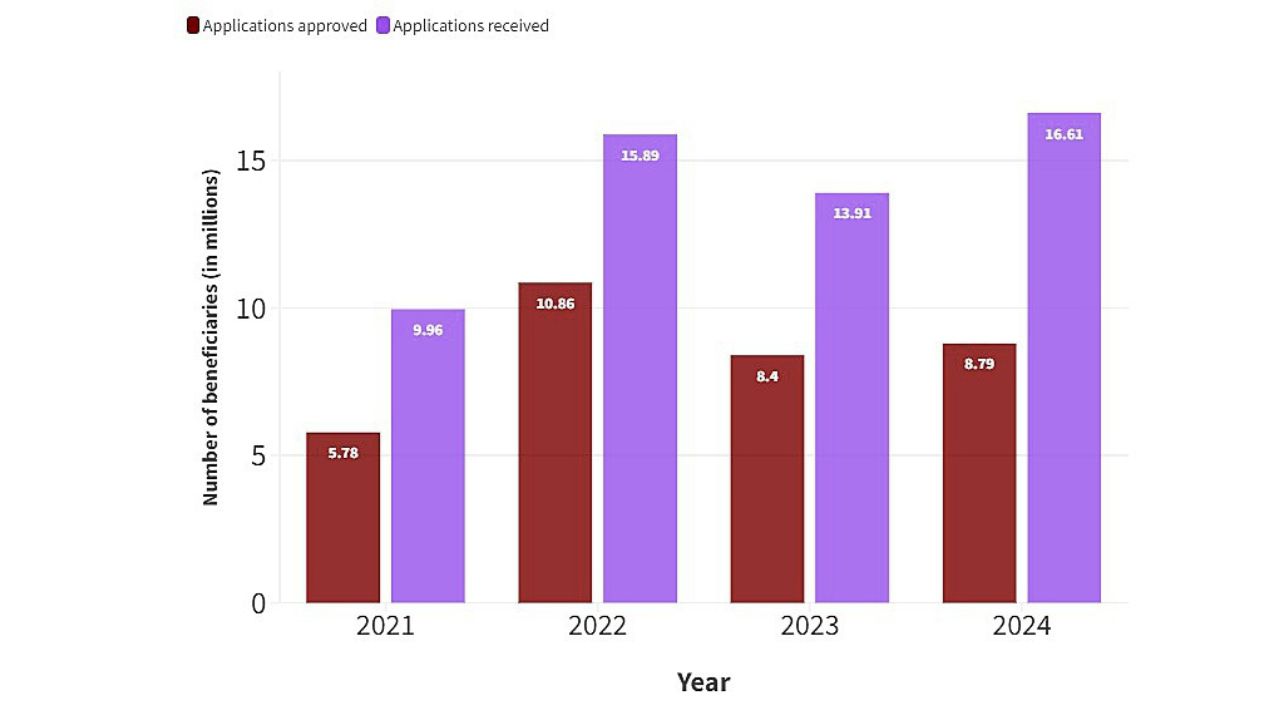

According to him, Sassa checks approximately 15 million SRD applications every month, and the amount of accepted beneficiaries varies between 7.5 and 8.5 million.

According to Van Vrede, Sassa has a “limited human resource capacity,” introducing manual procedures might result in staff strikes, which is detrimental to those needing help.

Van Vrede explained the appeals process, stating that applicants have 90 days to file an appeal on the DSD website if their application is denied. Payment processing for Sassa will occur if the appeal is successful. He also rejected the petitioners’ arguments that the document was unlawful.

Finance:

Edgar Sishi, the director general of the Treasury, stated in his affidavit that the restrictions do not infringe upon the fundamental right to social security. Sishi contended, “They provide the most coverage and protection to the most vulnerable South Africans that the state can afford at the moment and facilitate greater access to social security.”

Any court judgment that nullifies the restrictions might have “disastrous economic consequences,” he warned. Any such order must be halted so that the DSD minister can handle matters without putting a financial hardship on the finances.